Although there is no misunderstanding that drinking too much alcohol is harmful, the relationship between moderate alcohol use and health is complex. A new study1, published in The Lancet, analyses the daily alcohol intake that minimises health risks based on worldwide data. For individuals aged 40 years and older, drinking small amounts of alcohol seems to have some beneficial effects, but drinking more increases health risks. For younger people the amount of alcohol that minimizes health risks is zero or close to zero.

What is already known? The health risks associated with moderate alcohol consumption continue to be debated. Small amounts of alcohol might lower the risk of some health outcomes but increase the risk of others. A previous Global Burden of Disease study2 found that any alcohol consumption, regardless of amount, leads to health loss across populations. This study received quit some criticism from other scientists.3-7 On the other hand, a large multi-country study recently confirmed findings of previous studies that in comparison with lifetime abstainers, drinking less than one drink a day is associated with a reduced risk of dying due to any cause.8

What does this study add? This study1 provides a further analyses of Global Burden of Disease data to systematically determine thresholds for low-risk alcohol consumption while considering background rates of disease. The findings are the first to report alcohol risk by geographical region, age, sex, and year.

Method

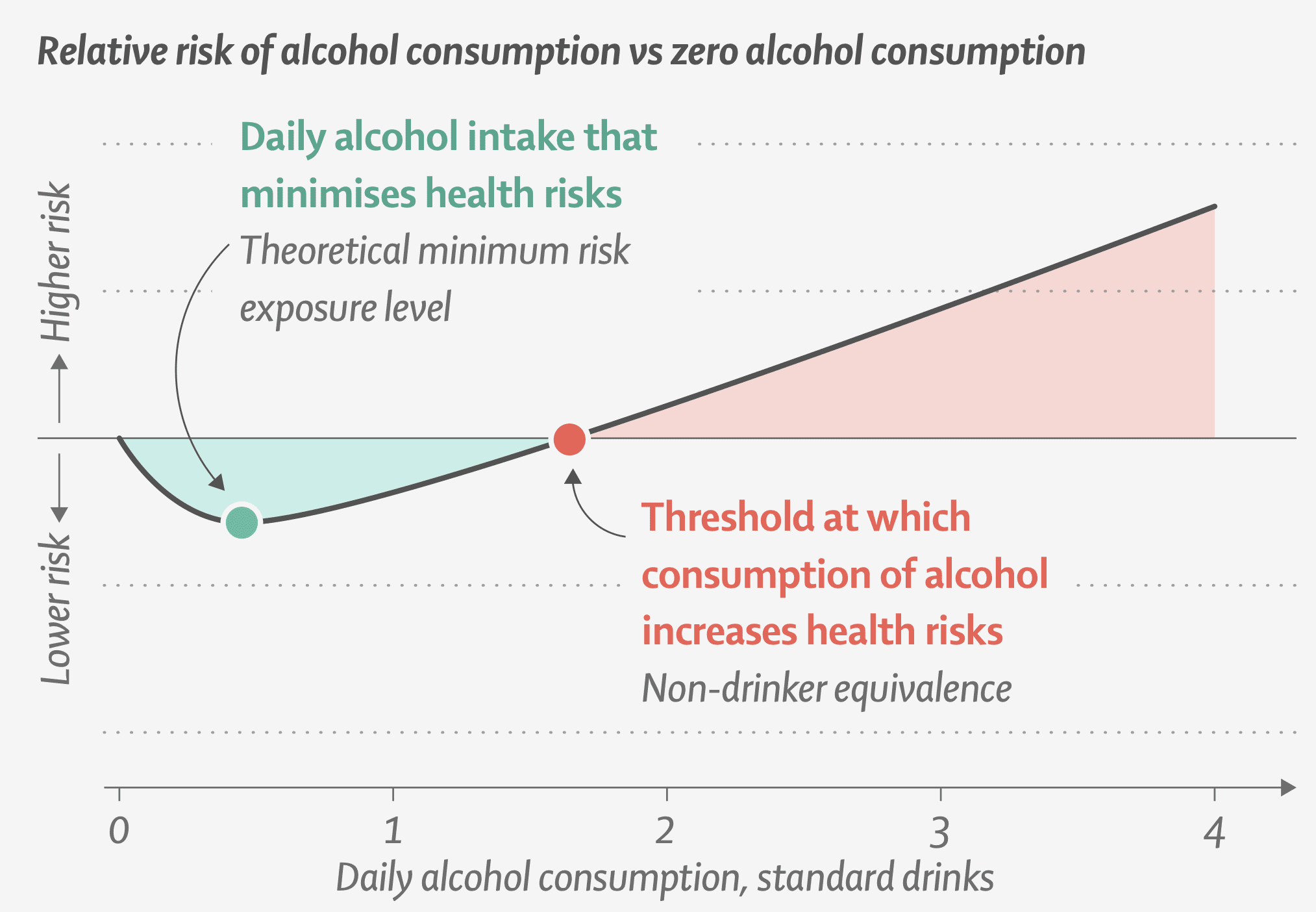

The researchers looked at the risk of alcohol consumption on 22 health outcomes, including injuries, cardiovascular diseases, and cancers, using 2020 Global Burden of Disease data including over 200 countries and territories. They used two important quantities: the theoretical minimum risk exposure level (TMREL), which represents the level of consumption that minimises health loss from alcohol for a population, and the non-drinker equivalence (NDE) level, which measures the level of alcohol consumption at which the risk of health loss for a drinker is equivalent to that of a non-drinker (see figure below).

Minimum risk level

Overall, the authors estimated the amount of alcohol that minimises health risks to be between 0 and 1.9 standard drinks per day. Levels of zero, or very close to zero, were observed among individuals aged 15–39 years ranging from 0 to 0.6 standard drinks per day. Higher levels were reported for individuals aged 40 years and older ranging from 0.1 to 1.9 standard drinks per day.

Risk compared to non-drinkers

Among individuals aged 40 years and older, the burden-weighted relative risk curve was J-shaped for all regions, with a NDE that ranged between 0.2·and 6.9 standard drinks per day. Among individuals consuming harmful amounts (more than the NDE) of alcohol, 59% were aged 15–39 years and 77% were male. The researchers therefore suggest that strictest alcohol guidelines should apply for men aged 15-39, who are at the greatest risk of harmful alcohol consumption worldwide.

Alcohol through life course

The level of alcohol that can be consumed without increasing health risks rises throughout a lifetime. This is driven by differences in the major causes of death and disease burden at different ages. Injuries account for the majority of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) lost among individuals aged 15–39 years. Any level of drinking leads to a higher probability of injuries. The alcohol-attributable burden shifts to chronic health conditions such as cancer in individuals aged 40–64 years. And cardiovascular diseases are the major causes of disease burden among individuals aged 65 years and older. Small amounts of alcohol decrease the risk of some conditions prevalent in older ages, such as ischaemic heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

Strengths

- Study takes into account the full epidemiological profile that includes the background rates of disease within populations

- Large amounts of data used for different countries, disease outcomes, age groups, men and women

- Adjusted for a lot of confounders including sick quitter bias

Limitations

- Observational research, cannot prove causality

- Pattern of drinking not included

- Based on theoretical mode

References

- GBD 2020 Alcohol Collaborators, Population-level risks of alcohol consumption by amount, geography, age, sex, and year: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2020.2022; 400: 185-235

- GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators, Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. 2018; 392: 1015-1035

- Comment from: Augusto F Di Castelnuovo, Simona Costanzo, Giovanni de Gaetano

- Comment from: Kevin D Shield, Jürgen Rehm

- Comment from: Arne Astrup, Ramon Estruch

- Comment from: Cedric Abat, Yanis Roussel, Hervé Chaudet, Didier Raoult

- Comment from GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators: Max Griswold, Emmanuela Gakidou on behalf of the GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators

- Di Castelnuovo, A., Costanzo, S., Bonaccio, M., McElduff, P., Linneberg, A., Salomaa, V., et al. (2021). Alcohol Intake and Total Mortality in 142,960 Individuals from the MORGAM Project: a population‐based study. Addiction.